#163: THE MOST BREATHTAKING BUILDINGS OF 2022

(photo from Adam Mork)

In 2017, I listed my all-time favorites. In 2019, I presented ten projects I called the most seductive. In 2020, the adjective used was most intriguing. In 2021, my essay displayed buildings that were the most striking. For the end of 2022, I highlight what takes my breath away. Defining breath-taking typically involves words such as awe-inspiring, astonishing, wondrous, and even out-of-this-world.

1: The western coast of Greenland offers the Ilulissat Icefjord Centre, both a research center and eloquent sculpture. Focusing on the study of massive glaciers and climate change, Dorte Mandrup’s design expresses the human condition within the science of ice, such as archeological artifacts contained in prisms of glass.

2: MVRDV’s “art depot” at the Museumpark, Rotterdam, comprises multiple exhibit halls, a rooftop garden, and restaurant. This Depot Boijmans Van Beuningen takes a behind-the-scenes approach by presenting all current works along with ones usually hidden in storage, both in full display. The architect sees the mirrored exterior as an innovative response to complementing the surroundings.

3: Google Bay View aims to operate the 42-acre campus on carbon-free energy by 2030. For Silicon Valley in Mountain View, California, a collaboration between Denmark’s BIG and England’s Heatherwick Studio created 1.1 million square feet of building, which includes an event center for 1,000, short-term accommodation for 240 employees, 20 acres of open space, and three main buildings covered in lightweight translucent canopy structures.

4: The project’s title, Origami House, is apt as this Barcelona house folds, creases, and rises out of the land adjacent to a forest and golf course. Designed by Office of Architecture in Barcelona, the paper white crispness and hidden service facilities (where are the stairs?) delivery a surreal composition, part home, part arts and crafts, and part dreamscape.

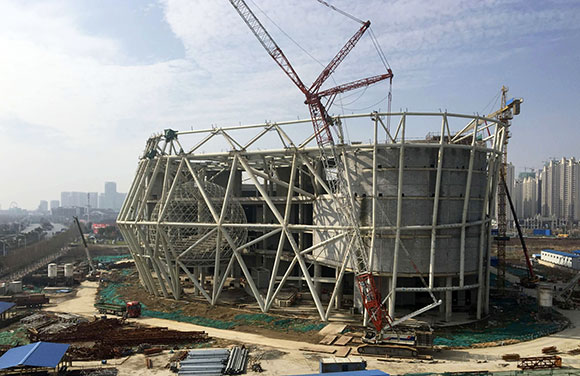

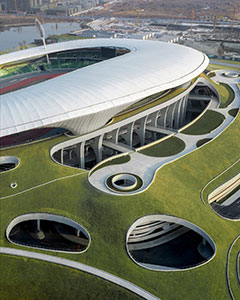

5: MAD Architects conceived the Quzhou Stadium in China as “a piece of land art.” Though with allusions to Bradbury’s science fantasy, this 30,000-seat stadium is no fiction. As an Earthwork, it links the worlds of art installation, landscape design, and architecture, while also straddling the visions of a mad man and artistic genius.

6: Since the 18th century, coffee has been a mainstay of Brazil’s economy. For the city of Carmo de Minas, Gustavo Penna Arquiteto & Associados deliver an iconic headquarters for CarmoCoffees. Introverted and introspective, save for the concave skylight, this warehouse for processing, tasting, and selling coffee explores the colors found in coffee beans.

7: Sou Fujimoto reinterprets nature at the Hungarian House of Music in Budapest’s City Park. Inspired by sound waves, the roof structure with its 100 Swiss cheese-like holes is both inspired by nature and “neo-nature.” The connection from inside to outside is exploited though a continuous translucent glass façade, like a candy wrapper.

8: Tens of thousands of aluminum pieces make up the high-relief exterior of the Museum of Modern Aluminum. Bangkok possesses a deep history of aluminum production, and he city of Nonthaburi became home to this 4,300-square-foot, prickly composition by HAS Design and Research. Serving as both a public space and urban getaway, the museum is viewed as an extension of the natural landscape offering contemplation on this busy street.

9: Different than the Rohe’s Farnsworth House and Johnson’s Glass house, both using glass in the vertical direction, Yung Ho Chang explores glass in the horizontal direction. Unlike the two renowned precedents which allow views out to the landscape, the Vertical Glass House focuses on viewing up to the sky and down to the earth. Located in Shanghai, China, the residence is poetic and ambitious, though with glass floors, perhaps impractical.

10: OMA often explores new types and forms of architecture. With the Taipei Performing Arts Center in Taiwan, the exploration reveals powerful results if not clumsily beautiful. OMA reversed the typical floor plan where the audience and performance spaces are central within the overall structure. Instead, the technical support spaces are now in the middle, and the audience is dramatically cantilevered on the exterior, hovering over public spaces, greeting the city’s fabric.

(For my recent list of faves in Los Angeles, visit here.)