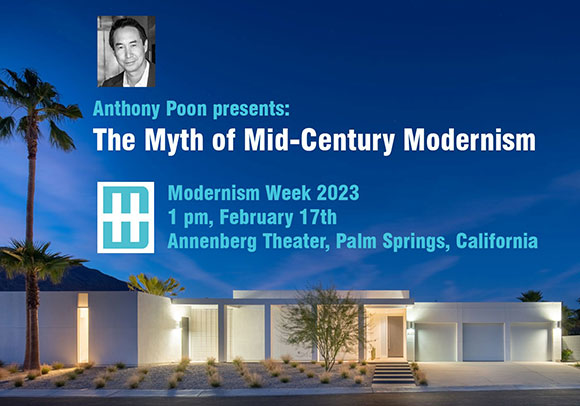

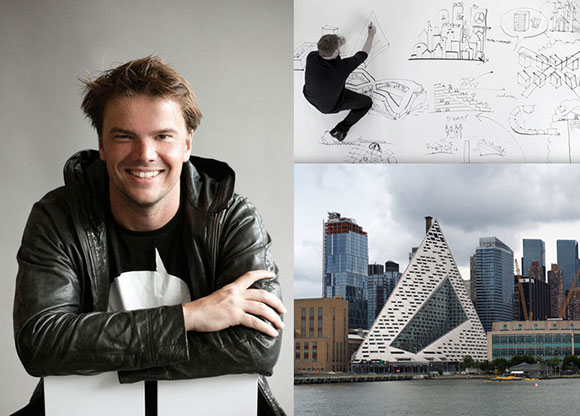

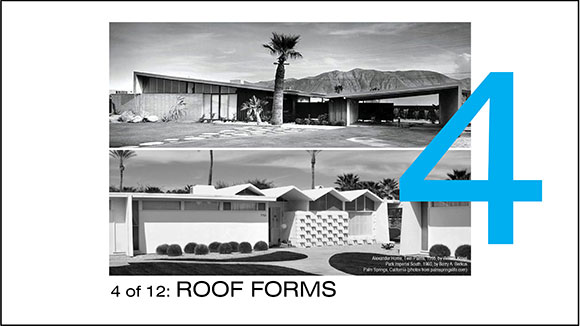

#167: MID-CENTURY MODERNISM: POINT OF DEPARTURE

Linea Residence G, Palm Springs, California (w/ Andrew Adler, photo by Hunter Kerhart)

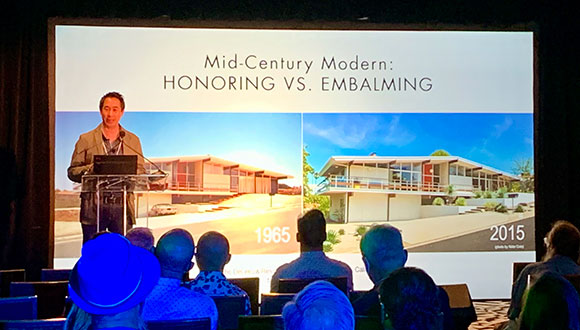

100,000 attendees descended on Palm Springs last month for Modernism Week 2023, the 10-day design festival celebrating Mid-Century Modernism (“MCM”). As a feature lecturer, I presented The Myth of Mid-Century Modernism—positing that we honor the design style of the 1950s and 1960s, but should not embalm it. For the thousands of MCM fans and fanatics, my position was blasphemous of sorts.

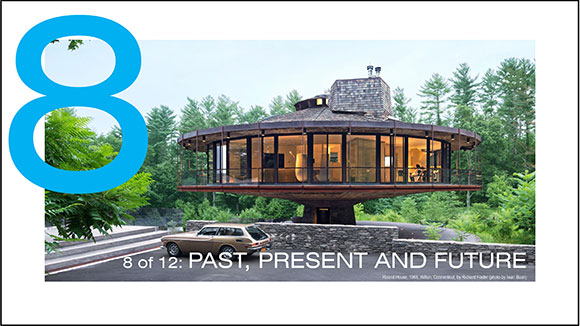

There are a dozen ideas from MCM that serve well as design themes—to be adapted not regurgitated. Acknowledge past legacies, but look forward not backward.

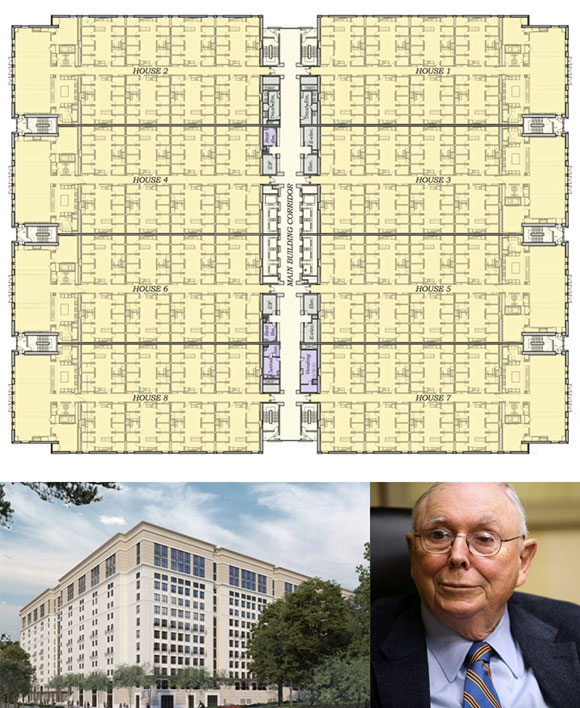

The MCM concept of the open floor plan countered the traditional compartmentalization of homes. At Poon Design, we applied the open floor plan to the design of a middle school. Rather than the conventional 12-foot wide by 10-foot tall, congested hallway lined with lockers, we created a 60-foot wide by 30-foot tall corridor—more a central atrium. Within sits the community functions open and accessible—library, math amphitheater, woodshop, and social areas.

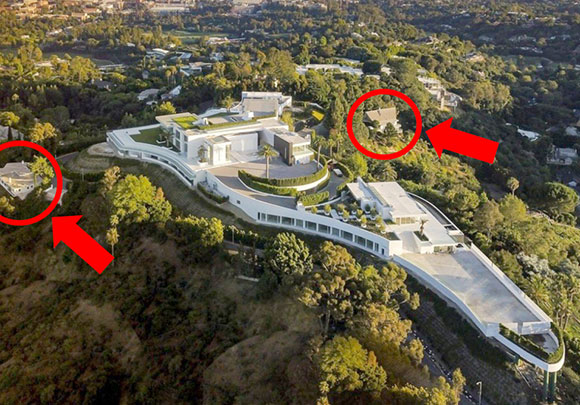

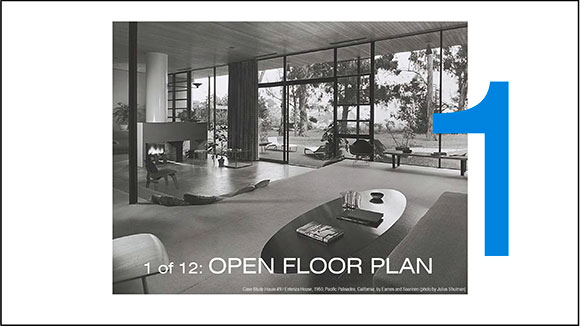

In California, we are blessed with moderate climate—not too hot, not too cold—that allows us to bring the outside in, blurring the division between interior and exterior. With today’s advanced engineering, the span of openings are wider. Technology even allows for sliding doors to disappear into walls.

Expansive walls of glass are prevalent in MCM homes. Here, we apply the ideas of lightness and transparency to a Buddhist temple. In the day, the walls of glass mirror the surrounding landscape, and at night, the glass disappears.

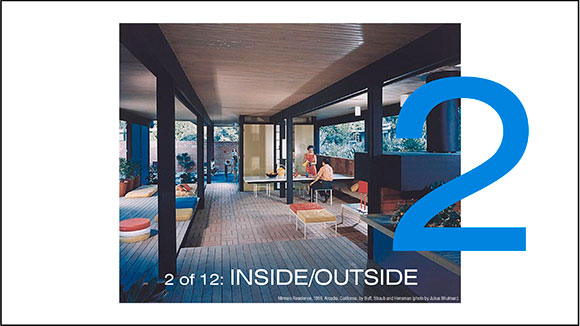

Often called the “butterfly” and “accordion” roof, we used such shapes not as an MCM gesture on a house, but as a unifying theme throughout a high school campus. Our roof lines recall the local mountains and serves as a metaphor for the institution’s mission statement, “Learning in Action.”

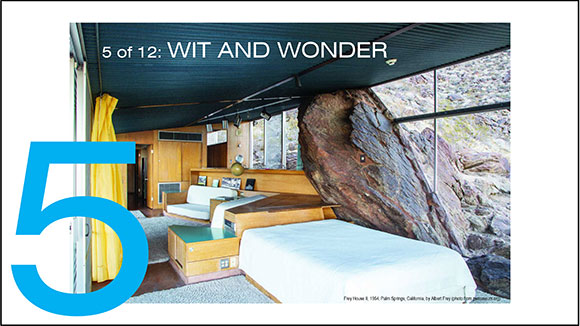

A restaurant can capture the imagination through wit and charm by applying 400 wood clothespins on chicken wire making a chandelier, faux grass expressing a new concept of the American picnic, and a mural-like chalkboard continuous from wall to ceiling.

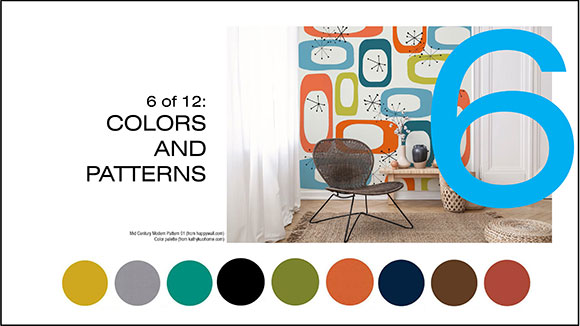

We enjoy the application of color and patterns, but not just as decoration—rather, to add personality to a space, to capture the spirit and character of the owner—whether a purple chocolate factory, red powder room, of multi-colored gymnasium.

Light can be more than simply a source of illumination. Consider light to be similar to stone, wood, or metal. Meaning, light can also be a building material. Light can be an element to be shaped, harnessed, and applied like a painter applies oils to a canvas.

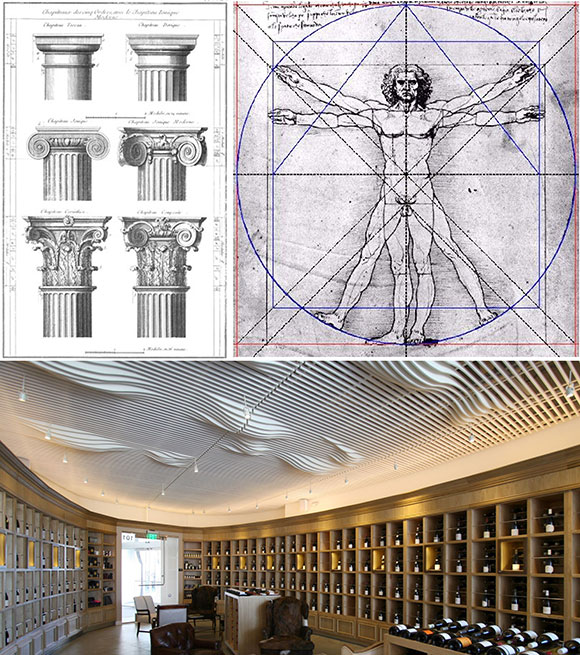

Having dominated architectural outcomes for centuries, the classical principles of architecture were open to MCM reinterpretation. At this wine store, the cabinetry possesses a traditional look with its cornice, trim and paneling. Yet, we applied such a traditional look to an elliptically-shaped showroom. Upon entering, the bottles of Bordeaux embrace the visitor.

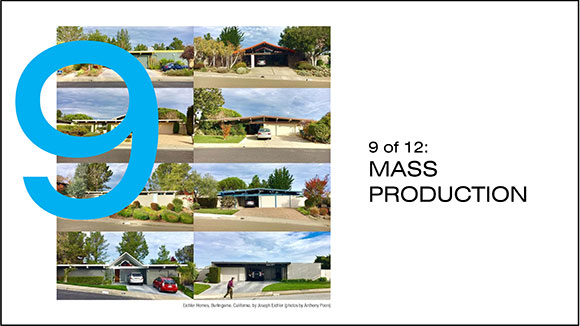

As the Case Study Housing program attempted, Poon Design also sought to provide attainable, budget-driven, mass produced homes. Building and selling 230 contemporary homes in four new Palm Springs communities has earned us the highest national honor from the American Institute of Architects, the 2018 Best in Housing, alongside dozens of other regional and national awards.

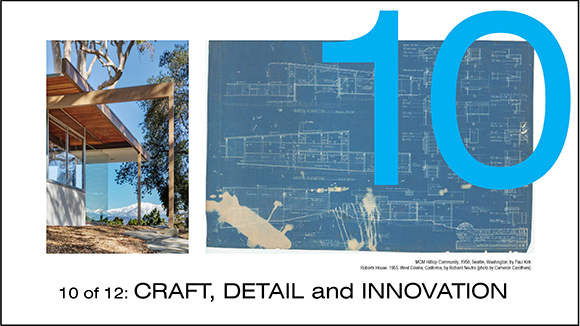

New tools and technology allowed us to exploit MCM’s drive for a high sense of craft. Giant lampshades at the famed Din Tai Fung restaurant reinterpret historic Chinese screens. Through computer scripted patterns alongside milling techniques of oak plywood, we created lampshades and skylights that are works of sculpture, expressing a devotion to detail and innovation.

MCM architects sought to provide design services combining three prominent strains: architecture, interiors and landscape. For our Chaya Downtown restaurant, we went further to deliver a cohesively designed environment. We created the branding, website, and graphics. We also designed furniture and lighting, as well as curated the art. We continued our pursuits to include the employee uniforms and even the selection of music. Music too is an element of architecture. What is heard during the morning hours of coffee is different than the business lunches—different than festive happy hour, different than an elegant dinner, and different than late night cocktails.

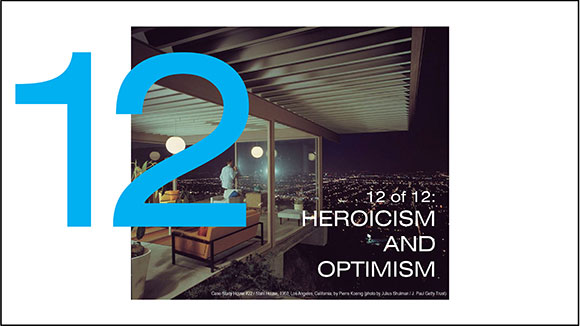

We continue the optimism of MCM at larger scales and more ambitious programs than housing. For this lifestyle center serving the Asian community, the first floor comprises an Asian fish market, the second is a Korean spa, the third a Japanese karaoke bar, and the fourth a Chinese rooftop garden restaurant.

The design concepts of Mid-Century Modernism endure, because they are timeless and universal. The challenge is to look to MCM concepts as a platform to launch into the future—as inspiration not as nostalgia, for interpretation not replication.