#154: WHAT IS YOUR BRAND?

Architecture by Zaha Hadid – upper left: Vitra Fire Station, Weil am Rhein, Germany; upper right: Library and Learning Centre University of Economics, Vienna, Austria; lower right: MAXXI: Museum of XXI Century Arts, Rome, Italy; lower right: Evelyn Grace Academy, London, England (photos from www.re-thinkingthefuture.com)

Whether a company, institution, or even an individual, it is imperative to establish a brand—a distinct identity, a unique look and feel that distinguishes from others. But whereas branding can help to establish a foothold in the marketplace, does it limit evolution of self?

Our retail and hospitality clients call their brand, “trade dress.” A corporation might brand their company identity through the enactment of a mission statement. However one’s brand is created and implemented, it can offer a road map, and others can join this journey knowing where they are going. Speak the company names of Apple, BMW, Disney, or McDonald’s, and everyone has a sense of that company’s brand, what they pitch, what is sold, and who we as customers consume.

On the other hand, an established brand can be like a straitjacket, restraining deviation and exploration that might lead to new opportunities. When Porsche, an automaker known for German efficiency and lean design, presented the Panamera, customers were baffled. This hulking sedan—more akin to an over-stuffed luxury vehicle than the agile Carrera—startled some, wondering what happen to the brand of Porsche. Was it risk-taking evolution or misguided brand confusion? The term “off-brand” reverberated in the halls of criticism.

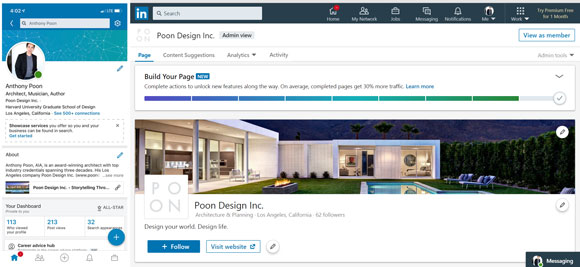

In art, consider the commercially successful works like Patrick Nagel’s soft-porn, male-fantasy caricatures (above) or Robert Longo’s thrashing individuals in business attire (below). Such art have reaped great exposure over the decades, from leading the pop culture zeitgeist to expanding in niche communities, to relishing a Renaissance of mainstream market presence. Some argue that the work, and that of many artists, look the same. But in the context of branding, repetition is not necessarily a bad thing, as it results in recognizability.

Man leaning back: Untitled (photo from pacegallery.com)

Women with hands over face: Cindy (photo from whitney.org)

Untitled (photo from redbubble.com)

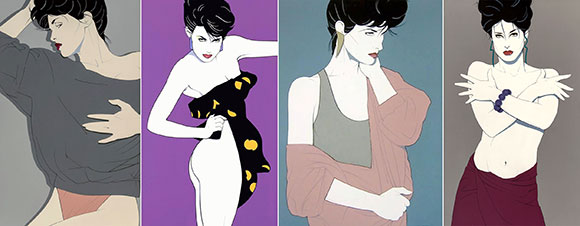

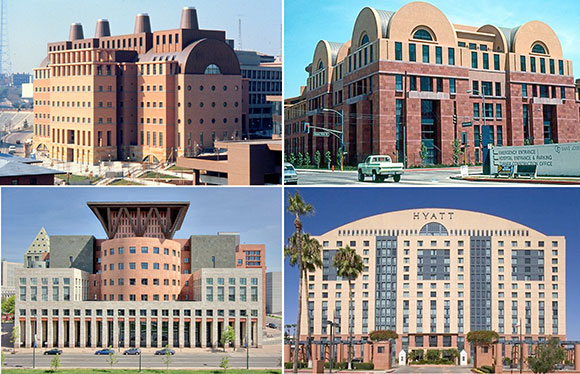

In architecture, companies big and small are branded as well. Some architects have developed a brand as a formulaic visual style. Others have branded their design process or a model of customer service. In the sphere of artistry, being predictable could be a death blow. But at times, cookie cutter processes can make for good business.

When an architect like Frank Gehry or Richard Meier (above), or actually any number of well-known designers, approach a project with the same road map resulting in what the building will look like, such formulas are profitable through their efficiency. For example, Meier doesn’t need to explore all the paint colors offered to him. He already knows that his building will be some shade of white. In business, this kind of brand saves times and makes the production swift. Clients don’t question the results much because they know the brand, and even expect it. The pitch is simple and evident from the start.

Same can be said with Michael Graves and his Post-Modern creations (above), Zaha Hadid’s extraordinary sweeping forms (at top), or Frank Lloyd Wright’s Prairie style (at bottom) .

But what about risks and experimentation? Evolution, artistic progress, improvisation —such things fuel the design journey, challenges the industry’s status quo, as well as internal agendas. Finding the right balance within the spectrum is the challenge—to create a brand that provides recognition and stability, while paving paths to an unknown future.