THE CURIOUS THING ABOUT STYLE, PART 1 OF 2

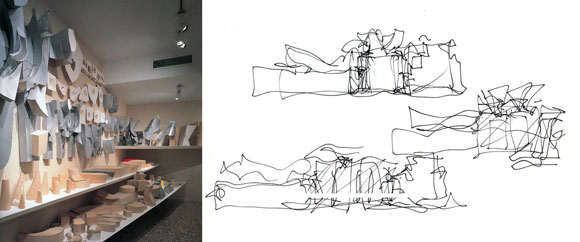

For this food blogger’s residence in Pasadena, we juxtaposed the technology of parametric algorithms on to polyethylene, the material used to make household cutting boards.

Recently, I was asked by an interviewer, “What is your style?”

This question is often asked, and not just of architects, but creatives of all sorts: fashion, graphics, advertising, cuisine, etc. The media typically aims to capture one’s design philosophy in a sound bite digestible by mainstream readers.

Many interior decorators have a packaged response. I hear words like “eclectic,” “warm and welcoming,” “contemporary yet timeless.” I am not sure what kind of design results from this mash up of clichés.

Architects have a hard time speaking of their style. Hugh Hardy, one of my past employers, argued that once you answer the dreaded question, your critics will constantly be assessing your work to see if you have lived up to your declarations.

What is style after all?

With extensive education, a higher degree and a 250-page graduate school thesis, many architects simply can’t and won’t summarize their creative philosophy in 20 words or less. For some, “style” is a bad word, and it shouldn’t be an elevator pitch.

Some colleagues who talk about their architectural style do so with clever labels. Steven Ehrlich, based in Los Angeles, calls his work “Regional Modernism.” New Mexico architect Antoine Predock is a self-described “Cosmic Modernist.” Herzog & de Meuron of Switzerland has been coined, “Elemental Reductivists.” From New York, Steven Holl’s work involves “typology, phenomenology and existentialism.”

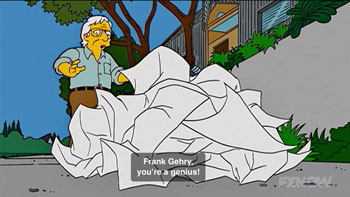

For architects such as Frank Gehry, Tadao Ando or Richard Meier, their style has been accused of being formulaic. Many would argue that all their buildings look the same. Is this so bad? Don’t all the Beatles’ songs and Beethoven Sonatas sound similar? (This topic of formula will be discussed in an upcoming blog.)

So now it is my turn to answer the universal question of style. My response should not be trite, but rather complex—but not pretentious.

I answered in two parts: Process and Product. My Process is inspired by jazz—the spontaneity and the improvisational spirit. (More another day.)

My Product, meaning the final structure, say a house or school, is driven by juxtaposition. I enjoy combining things together, either comfortably or awkwardly, to see what might arise: the modern and the traditional, the hand crafted and the machine made, the broad strokes and the finicky details, just to name a few.

For a Buddhist meditation retreat in Virginia, Poon Design created a guardrail that juxtaposed a galvanized off-the-shelf steel frame with natural twine made from hemp. Yes, you can smoke it.

For the University of California, our student center combined traditional campus brick and limestone, with sleek glass curtain wall and over-scaled weathering zinc shingles.

At Mendocino Farms, we blended a funky old school vibe, such as chalk board walls, vaudeville signage, clothespins, and industrial piping, with high-end luxury, such as Carrara marble, walnut planks, stainless steel trim, and custom furniture.

Juxtaposition is not just my artistic approach, but the interests in my life as well. I like Brahms and I also like American Idol. I like Rembrandt and Pop Art. I like omakase sushi with a Coke, as well as McDonald’s with sake. I wear Gucci with the Gap. Love Nan Goldin and commercial photography. I read biographies, but also comic books. I like watching ping pong and the Superbowl. Reality shows that follow CNN.

I like the diversity and the messiness. I like unexpected results.