THE WORLD FAMOUS FRANK GEHRY AND THE BEST JOB I DIDN’T WANT

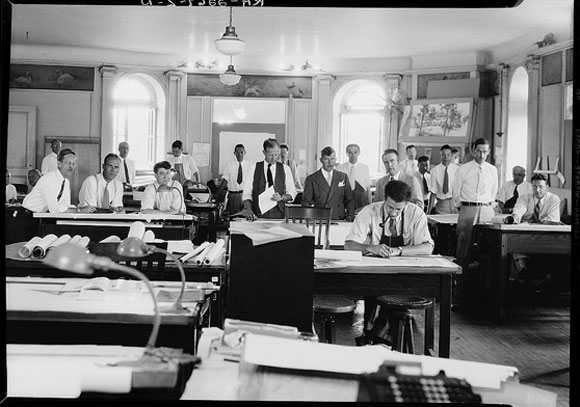

The Model Shop at Gehry Partners, Los Angeles (photo by Thomas Mayer)

I got the job! Unfortunately.

Not too many architecture companies were hiring during the economic recession of the 90’s. Though I held an impressive piece of simulated parchment that stated in fancy calligraphy, “Master of Architecture,” I could only find temp work as a paralegal, basically a data entry person.

After two years, one of my hundreds of resumes reached the right person. I received a call from the offices of Frank O. Gehry and Partners!

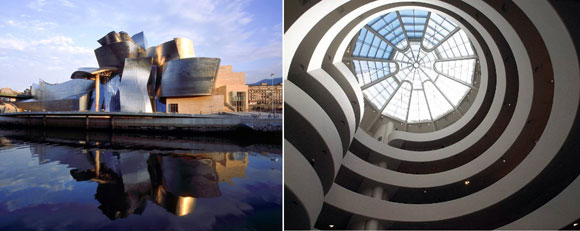

Yes. FRANK GEHRY. The formidable architectural genius of his generation. The most important American architect since Frank Lloyd Wright.

The Gehry interviewer welcomed me, shook my hand, and examined my resume. With tie and blazer, I sat there thinking my application was solid: noteworthy degrees, years of experience in San Francisco and New York City, and a handful of letters of rec. I had my portfolio as well, but as you’ll see, we never got to that.

Showing no indication of being impressed, the interviewer asked dryly, “Do you know how to use a table saw? A band saw? A palm sander?”

I smiled confidently, “Yes, of course.” But I was starting to see where this meeting was going.

I realized that I was not being interviewed for an architectural position, not even a drafting role. I was being interviewed for the infamous “Model Shop,” where young professionals set their egos aside and laboriously, meticulously produce physical models of Gehry’s designs. Some were beautiful presentation models with the quality of fine furniture. Some were rough studies of an inkling of an idea that the genius architect dreamt up in his sleep.

Nonetheless, I swallowed my pride. I needed a job that was in my field, regardless of whether I was designing one of Gehry’s concert halls or emptying his trash can. Regardless of the backward step for my career arc, I expressed my most convincing enthusiasm about joining this Gehry organization. After all, my updated resume would carry one of the grandest architectural names of all time.

The interviewer congratulated me, “Okay, you got the job!”

Starting pay was a generous $8 an hour. Adding insult to injury, the interviewer then laid out the terms. Every year, each Model Shop employee gets an automatic raise. That sounded promising, until, with a weird congratulatory wink-wink-smile, he added, “Each year, you get 25 cents more on your hourly rate.”

(Was this a joke? Did I hear wrong? I calculated that it would take me 16 years to get back to the salary of my first job as an entry-level architect in New York.)

I pushed back all the warnings in my head, and replied, “I would be honored,” again delivered with a convincing tone. I could not return to being a paralegal temp.

The tipping point was not a point, but a blow.

When the interviewer asked me when I could start the job, I responded, “In a week.”

“No, it must be much sooner,” demanded the interviewer.

I squealed, “How about in three days?”

He pressed, exclaiming, “No, even sooner.”

It was past 9 PM. The interviewer announced his command. “We have many deadlines, and I need you to take off that tie.” He pointed to a stack of plywood surrounded by tools, and with no wink-wink this time, he asserted, “Start your job NOW.”

At this point, the magic of the Pritzker-Prize-winning, AIA Gold Medalist Frank Gehry evaporated like a handprint on the surface of water.

I picked up my unseen portfolio, rejected the offer, and left the offices of Gehry. With my tie still on.

Within a year, I officially launched my own firm. Yes, my company also has a model shop. Just this morning, I used the band saw to cut my own pieces of plywood.

For more, read my review on the Gehry retrospective at LACMA.