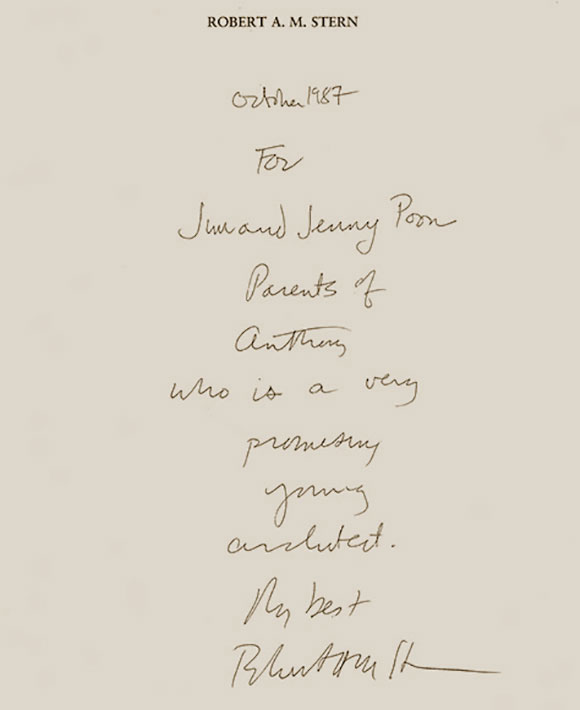

#216: TRIBUTE | ROBERT A.M. STERN (1939-2025) AND THE BEST OF TIMES

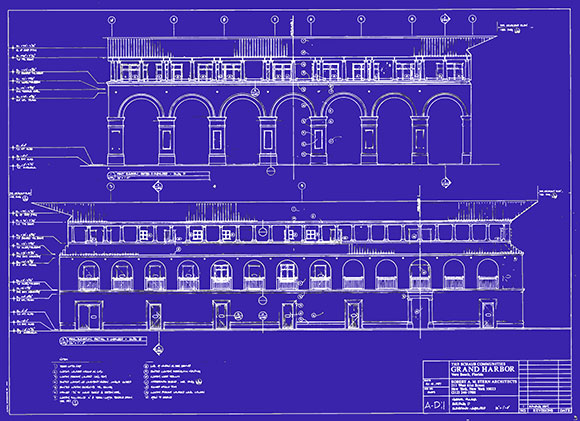

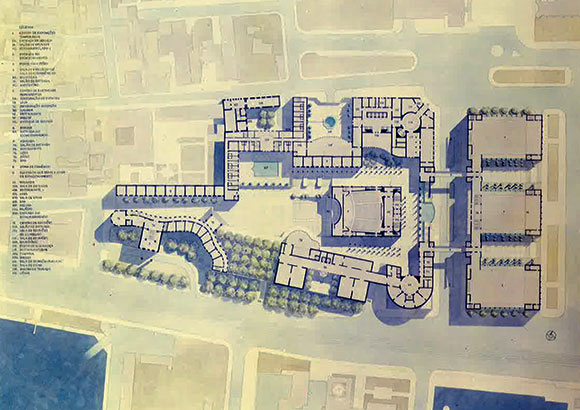

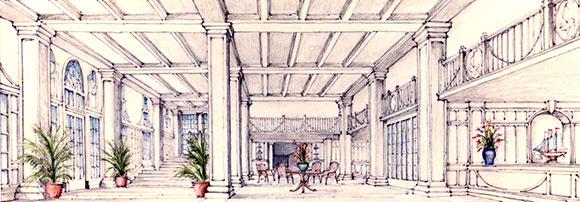

Clay model study, Grand Harbor Community, Vero Beach, Florida (model by RAMSA model studio, photo by RAMSA)

I didn’t know what to expect when I got the phone message. It was the late 80s. I recently graduated from architecture school, relocated from California to New York, and worked at a no-name corporate firm in Midtown Manhattan. Surprisingly, I received a job offer through voicemail from the famed Robert A.M. Stern Architects (“RAMSA”). Accepting the offer, I felt a little guilty jumping that no-name ship. But it wasn’t much of a Sophie’s Choice: staying at a generic architecture company vs. joining a leading voice of the groundbreaking Postmodern movement.

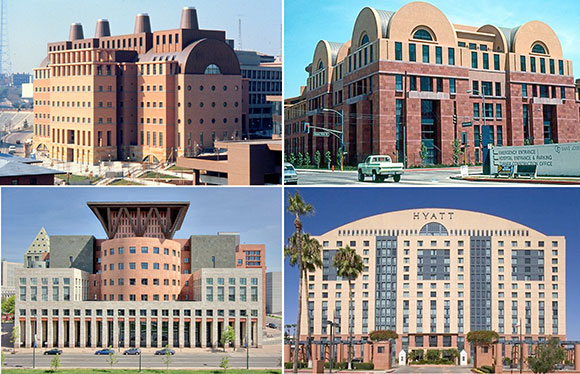

When an undergraduate student, my colleagues and I crammed into a car to cross the bay from Berkeley to San Francisco to the Fine Arts Museum—to hear Mr. Stern articulate his provocative thoughts on Postmodernism. This topic was not only the cutting edge design philosophy at the time, but the center of our architectural studies. Opinionated and charismatic, Stern inspired us with words and images of grand residences in The Hamptons. In a somewhat traditional Shingle Style of the late 1800s, his designs possessed a wry twist—either of wit and humor, a contortion of proportions, or an irreverent use of classical motifs. These were not just houses, but philosophical critique and commentary.

Little did I know that a few years later, I would be employed by this Robert A.M. Stern. At the office, it felt like a privilege to call him simply “Bob.” Like calling Robert Mapplethorpe, “Rob.” Or David Bowie, “Dave.”

Bob’s reputation intimidated us 20-something architects, but though he was astutely opinionated, he was accessible, always ready to chat with new employees and fresh minds. He engaged both the Big Picture—the importance of architecture and who it serves—as well as the details—the profile and proportions of a roof cornice, for example.

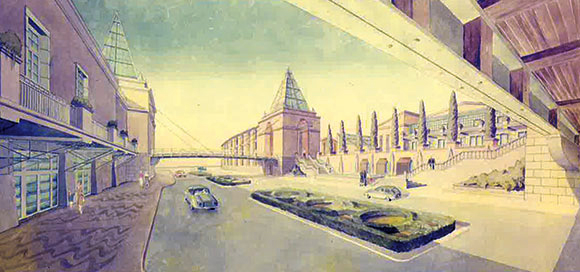

In hindsight, the opportunities at RAMSA now seem like unbelievable gifts of opportunity. For the competition to design a cultural center in Lisbon, Portugal, I was personally given the chance to design an entire city complex. I was not just drafting a senior architect’s ideas, but rather, I was actually drawing hands-on my own ideas for Bob’s review and endorsement.

And for this project, I worked day and night. Literally day and night. Over the final week, I worked an average of 20 hours a day! At the enthusiastic age of 23, one can actually work 20 hours then race home to a studio apartment to nap, shower, and change, then return to work. Some might think of this as employee abuse or a reason to check in with a labor attorney, but for me, the creative adrenalin kept me going for days—and with a smile and gratitude for such an opportunity. Though we didn’t win the commission, Bob, our gracious host/employer, treated the team to a five-star dinner (Le Cirque Brasserie, I think). I wore my newly purchased grey, double-breasted suit from Giorgio Armani.

One weekend, Bob invited RAMSA employees to the celebration of Michael Graves’ 25th anniversary teaching at Princeton. I witnessed a rare panel discussion between the rising Starchitects of the time. During the deliberation: Bob viewed the work of Frank Gehry through the lens of historicism; Gehry expressed confusion over “deconstruction vs. deconstructionism vs. deconstructivism”; and surprising Michael Graves, Peter Eisenmann claimed that though architecture is subjective, there are rights and wrongs in architecture. He argued, “If one is supposed to go up, you don’t design a stair that goes down!”

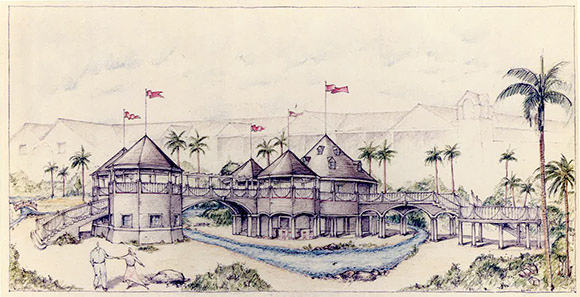

When master planning Euro Disney in 1987 (now Disneyland Paris), Bob invited the most influential architects of the time to collaborate on this grand project. I came into the office that extraordinary weekend to watch Bob design alongside Frank Gehry, Robert Venturi, Michael Graves, and Stanley Tigerman. Knowing such an event could either be a teamwork or clash of titans, Bob moderated with grace, intelligence, and diplomacy.

The pace never slowed. During the Christmas season, Bob was invited to team with Calvin Klein and design one of the famed holiday windows at Bergdorf Goodman. World-famous architects joined world-famous fashion designers to create a 5th Avenue streetscape of festive artistry.

I was employee number 100. When I left, RAMSA grew to 150 employees. During my short time there, I only got to know Robert A.M. Stern briefly, but the many experiences created the most treasured recollections a young architect could ask for.